GEORGE WASHINGTON SPEAKS BLOG ARTICLES

OUR ARTICLES ARE CURRENT SO CHECK BACK AND KEEP UP ON OUR EVENTS AND NEWEST VIDEOS.

Have you ever wondered how George Washington came to be the trusted leader of the American Revolution and the new nation? What early experiences molded him and shaped his character?

The George Washington Speaks website includes nineteen videos on Washington’s family background and early life. Born at Wakefield, his family’s plantation on Pope’s Creek near the Potomac, Washington was a farm boy from birth. Throughout his life, he lived in the plantation environment of raising and selling crops, with much of the labor by enslaved people.

His family moved to Ferry Farm, near Fredericksburg, Virginia, when George was about six. Most of his youth was spent there. Consider how these events might have influenced his character and development:

His father’s community leadership and business ambitions

– A devastating fire at the Ferry Farm

– His father’s death when George was eleven years old

– Years in poverty, and lost opportunity for education, after his father died

– Greater responsibility as a youth, to help support his widowed mother

Because Ferry Farm barely produced enough to support the family, George sought other opportunities. At age sixteen, he trained in surveying using tools left by his father. He took some payment in land—mostly undeveloped property—and accumulated holdings in his own name.

His older brother Lawrence married into the prominent Fairfax family, and introduced George to the society of Virginia’s upper gentry. Though he was painfully shy, these relationships helped him develop social skills that served him well throughout his life.

I hope you will view and share the videos on our website—especially with teachers and students of American History.

Contact me anytime at [email protected].

I am your servant,

Vern Frykholm

SURROUNDED BY PATRIOTS

George Washington didn’t live in a vacuum, and I cannot develop a clear picture of his life and times without learning something about the people around him. These include other colonial and national leaders as well as the men who served in the Continental Army, sharing the fight for freedom that Washington led.

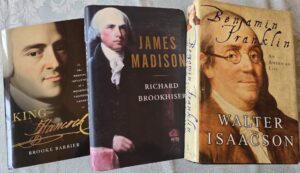

Some are household names in America, like John Hancock, famous for his bold signature on the Declaration of Independence. He is the subject of a 2023 biography by Brooke Barbier, titled King Hancock: The Radical Influence of a Moderate Founding Father.

Hancock and Washington were close in age, but grew up in vastly different circumstances—except for one. Both men lost their fathers at a young age. I look forward to delving into the details of Hancock’s life, and how he came to the Patriot cause.

Ben Franklin was a generation older than Washington and Hancock, and grew to prominence in Philadelphia as a newspaper editor and printer. But he had his hand in many pots, and Walter Isaacson’s biography, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life, reveals much about his interests in science, government, and international affairs.

James Madison was nineteen years younger than Washington, part of a generation who would carry the country through another war—with Madison as president this time. Richard Brookhiser’s biography James Madison fills in the details, from a young Madison’s admiration for Washington to his own service at the highest level.

It would be a mistake to limit myself to the elites of the Revolutionary period, because the stories of ordinary citizens offer a valuable view. The wartime diary of James Plumb Martin, republished as Private Yankee Doodle in 1962, offers a foot-soldier’s account of life during the war. His colorful prose is entertaining and detailed.

I’m always looking for more to read about 18th century America, so if you have a recommendation, please let me know, via email to [email protected].

WELCOME OUR GUEST LARS HEDBOR

This month we welcome acclaimed Revolutionary War novelist Lars Hedbor to the blog.

The American War of Independence Around the World

by Lars Hedbor

POP QUIZ!

Which of the following were locations where incidents directly connected to the American War of Independence took place?

a) Bermuda

b) Senegal

c) The Rock of Gibraltar

d) San Juan, Costa Rica

e) Pensacola

f) Minorca

g) Cuddalore, India

h) All of the above

If you answered “All of the above,” you were completely correct!

Why were so many nations involved?

The American War of Independence rapidly grew beyond a confrontation between American rebels and the British Crown, with the French entering the war allied with the future United States, and Spain declaring war on Britain in alliance with France. As all three colonial empires had holdings and interests across the globe, the war came to have a global scale.

Highlights from the 18th century “World War”

The Bermuda Powder Raid of 1775 involved Bermudan businessmen, who were both sympathetic to the American cause, and eager to restore trade with North America. After brokering a secret deal with Ben Franklin, they broke into the Crown’s store of gunpowder and handed the powder over to ships sent by the Americans. Most of what we know about this incident comes from the outraged proclamations and official letters sent by the loyal British governor, and despite substantial rewards, none of the plotters were ever definitively identified.

In 1778, French forces retook the capital, Saint-Louis, of Senegal, their former colony in West Africa. The British had taken Senegal in 1758 during the Seven Years’ War (known in North America as the French and Indian War), and France was eager to restore their dominion over the colony.

The Rock of Gibraltar was the scene of the longest siege in history, with the French and Spanish attempting in vain to seize this crucial outpost at the mouth of the Mediterranean from Britain. As many as 33,000 soldiers and 30,000 sailors besieged the island from June of 1779 through February 1783.

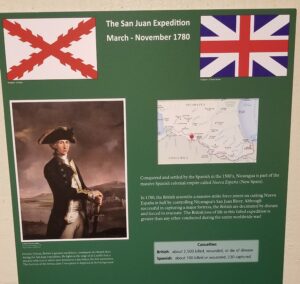

The later infamous British naval officer Horatio Nelson, along with Major John Polson, undertook a campaign in 1780 to take Granada, in the Spanish province of Nicaragua, in order to divide Spanish holdings in the Americas, and gain access to the Pacific Ocean. Despite success at Fort San Juan (today part of Costa Rica), the force was decimated by yellow fever, and with the loss of 2,500 men, the San Juan expedition was the greatest British disaster of the war.

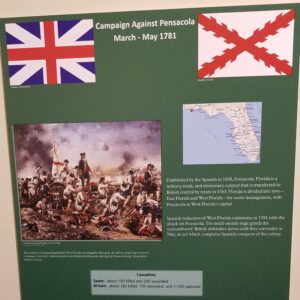

Pensacola, in modern-day Florida (and then part of the loyal British colony of West-Florida), was besieged and taken in 1781 by the Spanish under the heroic leadership of Bernardo de Gálvez, in the culmination of his incredible campaign along the Gulf Coast to deny the British access to attack American forces from the West.

The Mediterranean island of Minorca was seized by a joint French and Spanish force in 1782, and was ceded to the Spanish at the end of the war. The British retook it in 1798, but it returned to Spanish hands in 1802, where it remains today.

The Siege of Cuddalore, India was the very last confrontation in the American War of Independence, pitting British and French-allied forces against each other in India. The siege took place in 1783, after the signing of the Treaty of Paris that ended the war, but before word of the peace had reached the distant outposts in India. It ended when news of the outbreak of peace reached them, bringing the long war to a final – if little-known – conclusion.

***

Thank you, Lars! At Saratoga National Historical Park in New York, I saw a wonderful display about the worldwide reach of the American Revolution, including the photos above. I recommend a visit. Vern

About Lars D. H. Hedbor

Hedbor is the leading novelist of the American Revolution, with sixteen books in print, each of which is set in a different colony or future state. In addition to writing about Bernardo de Gálvez’s Gulf Coast campaign in The Wind, his most recent novel, The Powder, is a telling of the story of the Bermuda Powder Raid. You can find more about Hedbor on his Web site at larsdhhedbor.com. His books are available at all online booksellers, and are published in ebook, paperback, hardcover, and audio formats. To get signed and personalized copies of his books, you can go to tfar.us/shop.

WELCOME OUR GUEST STEPHANIE DRAY

We are delighted to welcome our guest, bestselling author Stephanie Dray, to the blog this month.

Washington in the Round: Exploring a Legend Through Fiction

by Stephanie Dray

Vern with Stephanie Dray (left) and co-author Laura Kamoie at the 2019 Historical Novel Society Conference in Maryland.

In the rich tapestry of American history, the persona of George Washington looms as a colossal figure. He’s on Mount Rushmore, the nation’s capital bears his name and is ornamented by a giant monument. But as with all the iconic figures of American history, the perception of this leader varies dramatically depending upon the lens through which he is viewed.

In times of continued racial tension, it is right to remember that he was a slaveholder. In times when presidential candidates talk about how we ought to have a president for life, it is right to remember that George Washington relinquished his power, refused to be king, and set in motion the democratic principles that have served our nation for more than two centuries.

But Washington doesn’t just look different depending on the angle from which we’re viewing him. He also looks different from the vantage point of his contemporaries.

In my novel, “America’s First Daughter” co-authored with Laura Kamoie, the American Revolution and the early years of the country are seen through the eyes of Martha “Patsy” Jefferson Randolph. For Patsy, her initial understanding of the American Revolution is deeply intertwined with the actions and beliefs of her father, Thomas Jefferson. George Washington, in this narrative, is a secondary figure, much overshadowed by the more direct influence of her father, especially his role in crafting the Declaration of Independence.

As Patsy matures, of course her perspective shifts. In the early years of the new nation, she more likely observed Washington not as a detached historical figure but through the lens of her father’s political struggles, particularly with Alexander Hamilton. Washington, from the point-of-view of the Jeffersons, emerges not as the unassailable hero of popular imagination but as a leader entangled in the complex web of early American politics, seemingly unable to rein in Hamilton’s influence.

In “My Dear Hamilton”, a different view of George Washington emerges, as seen through the eyes of Eliza Hamilton. For Eliza, Washington is a figure of deep reverence and admiration. The Hamiltons, and Eliza in particular, idolized him not only for his exemplary leadership but also for his integrity as a role model.

It is his character as a gentleman that deeply resonates with Eliza as he balances the heavy weight of the war upon his shoulders. He exudes a sense of honor, dignity, and a profound sense of duty. Their interactions are marked by Washington’s respectful and measured demeanor, a stark contrast to her much more intemperate husband, Alexander Hamilton.

However, a notable moment of tension arises when Washington refuses to grant Hamilton a military command, leading to a dramatic rift. Despite this, Eliza remains eager for reconciliation, her esteem for Washington undiminished. She sees him not only as the epitome of the American hero but also as a leader who embodies the values and aspirations of the new nation.

This multifaceted portrayal highlights Washington’s influence not only through his public deeds but also through his personal virtues. And Eliza perpetuated the legend of George Washington through her work on his national monument. As the musical says, she told his story. And she told it because she knew him personally.

The entwining of the personal and the political in forming an opinion about George Washington was even more evident when I was writing “The Women of Chateau Lafayette.” Through the eyes of the Lafayette family, particularly Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, and his wife Adrienne, Washington is a father figure–a mentor who provided guidance and inspiration during the Revolutionary Era. The couple even named their first son after him. This familial sentiment deeply influences how the Lafayettes live their lives, not to mention how they perceive Washington, framing him as a person of great significance beyond his public persona.

However, when Lafayette is imprisoned during the French Revolution, Adrienne’s frustration with Washington’s seemingly indifferent response to their plight seems justified. While historically, Washington was navigating a delicate balance of American interests, his lack of support for the Lafayettes during their time of need paints a picture of an emotionally cold leader caught in the throes of geopolitical pragmatism.

Which of these versions of Washington is the correct one? Perhaps all of them. But I look forward to seeing Washington through yet another set of eyes in our forthcoming novel “A Founding Mother” about Abigail Adams and her daughter Nabby.

BIO

STEPHANIE DRAY is a New York Times, Wall Street Journal & USA Today bestselling author of historical fiction. Her award-winning work has been translated into ten languages and tops lists for the most anticipated reads of the year. She lives in Maryland with her husband, cats, and history books.

www.StephanieDray.com

While most of my George Washington research falls in the non-fiction area, I do enjoy the fictionalized stories of our founding era. My wife and I have read all of Stephanie Dray’s novels of the period, and look forward to reading more. Vern